#8 Navigating America's Aging Network : The Infrastructure of Aging-in-Place

Inside the public backbone supporting 12 million older adults aging-in-place—and why AgeTech investors and founders should pay attention,

The stat is well-known and frequently repeated: Most older adults (about 75%) would like to age in place.

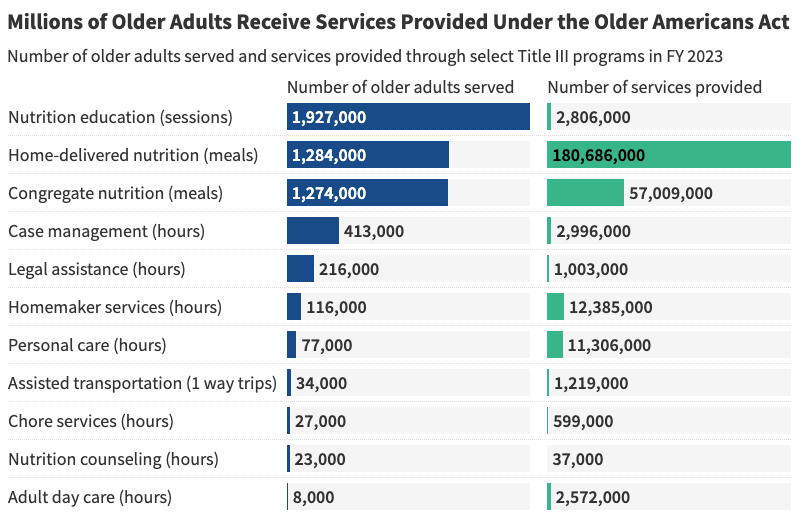

In the US, the “Aging Network” of over 600 local agencies helps to make this possible. The group collectively supports one in six older adults by providing critical services outside the context of institutionalized care, ranging from meal services and in-home assistance to caregiver support.

Unfortunately, the Aging Network runs on local government, Medicaid and Older Americans Act (OAA) funding, all of which are frequently subject to review and have not kept pace with the growth of older populations in recent years.

As demand surges and budgets tighten, agencies within the Aging Network are being forced to do more with less. This is accelerating a quiet transformation: many are looking to adopt new technologies that can boost efficiency and seeking new partnerships (particularly with healthcare) to diversify revenue as well.

For AgeTech founders and investors, this shift opens a rare window to modernize a trusted but under-resourced public system, and to scale solutions that directly support the future of aging in place.

Aging Network 101

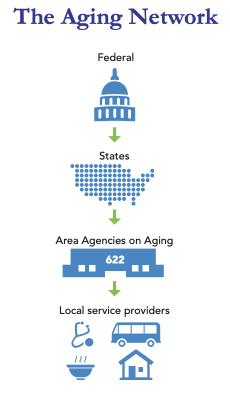

Created by the 1965 Older Americans Act (OAA), the Aging Network is a three‑tier public system:

Federal – The Administration for Community Living (ACL) allocates funds across seven program areas known as “Titles.” Two important ones to know are:

Title III includes funding for supportive services (transportation, case management, information access points), nutrition services (congregate and home-delivered meals), disease prevention and health promotion, and caregiver support

Title IV has discretionary and competitive grants to fund research and demonstration projects for innovation in aging services

State – 56 State Units on Aging draft multi‑year plans and decide each state’s intrastate funding formula to determine how federal funds are distributed within their state.

Local – 618 Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) plus 250 Tribal programs deliver or subcontract the services, which range from meals, transportation, caregiver support, home modifications, and more.

AAAs are a diverse group of organizations designated by states to coordinate and deliver services that help older adults age-in-place. They can be either government, nonprofit or tribal organizations. For a start-up, AAAs are typically the groups that they would first sell into within the Aging network.

Why the Aging Network is Under Threat

Despite their reach, the Aging Network operates under chronic funding pressure. Practically every AAA out there will say that funding is their #1 concern.

Federal OAA grants are discretionary and have not kept pace with rising demand. Recent reauthorization efforts have also struggled to advance, leaving agencies without certainty for future OAA funding.

And while Medicaid funding contributes as an alternative, it rarely aligns perfectly with the Aging Network’s scope and is often fragmented across programs, states, and eligibility rules. Additionally, the newly passed 2025 federal budget reconciliation bill will put more pressure on states cut costs in its Medicaid programs as their capacity to raise revenue is constrained.

New Revenue Avenues Needed

New partnerships present important alternative sources of funding for AAAs seeking to diversify in these challenging times. But tapping into these opportunities increasingly requires stronger data systems and the ability to demonstrate measurable outcomes.

Historically, it had been less common for the Network to articulate its value through standardized data. A 2018 poll by the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging found that only 28% of AAAs measured the financial value of their services while the remainder did not. This can make outcomes harder to quantify and funding feel more discretionary.

Today, pioneering AAAs are working to change that. By aligning with new stakeholders, they are adopting more rigorous data practices to secure sustainable, performance-based funding.

Medicare Advantage

To offset constrained federal dollars, AAAs are increasingly partnering with Medicare Advantage (MA) plans. Nearly 45 % of AAAs now report at least one healthcare contract, but this has historically been within Medicaid as opposed to MA. As of 2023, only 24% of AAAs contract with MA plans.

Entry often starts with care‑transition coaching programs that cut 30‑day readmissions—exactly the metric MA plans reimburse. Anecdotally the impact of combining clinical and social teams for care transition programs can be very significant as hospital readmissions represent significant costs for MA plans.

Housing Partnerships

Developers of senior and mixed‑income housing are realizing that AAAs can lower tenant turnover and improve property values. A Michigan AAA secured service funding from a HUD‑supported developer by embedding a full-time care coordinator in a 45‑unit project. Federal initiatives like the Housing & Services Partnership Accelerator are scaling such cross‑sector models between housing and aging services.

Start-up Landscape

While historically slow to adopt new tools, AAAs are increasingly turning to technology out of necessity. The convergence of labor shortages, growing demand, and a heightened need for data-driven documentation is pushing even the most cautious organizations to seek innovative solutions that 1) improve efficiency and 2) relieve documentation burden.

While start-ups may face challenges working with resource-constrained groups like AAAs, there are important reasons why this space should not be overlooked:

High-need, low-tech infrastructure. The Aging Network already supports millions, but with outdated tools and limited tech capacity.

System under pressure. Rising demand, workforce shortages, and flat federal funding are driving urgency to modernize.

New payer pathways mean new capabilities needed. AAAs are opening contracts with new partners, notably MA plans, requiring them to build up new capabilities quickly.

Given the opportunity, below are two of the start-ups leading the way in creating tech solutions to serve the Aging Network:

Mon Ami – Volunteer‑coordination and case‑management software used by 80+ AAAs across 27 states. Helps streamline I&A workflows and friendly visitor coordination.

Blooming Health – Multilingual communication platform (SMS, voice, email) that improves outreach and engagement

Closing Thoughts

The U.S. already has the scaffolding to support aging in place. What it lacks is modern tooling and sustainable funding. Technology has a critical role to play in bridging this gap: improving service delivery, tracking outcomes, and unlocking partnerships that make the system more resilient.

For AgeTech founders and investors, this is an opportunity to build the operating system for “Aging-in-Place” on top of a trusted infrastructure that already serves millions.