#11 What is the Alzheimer's Tech Stack? Looking at Tools Across the Patient Journey

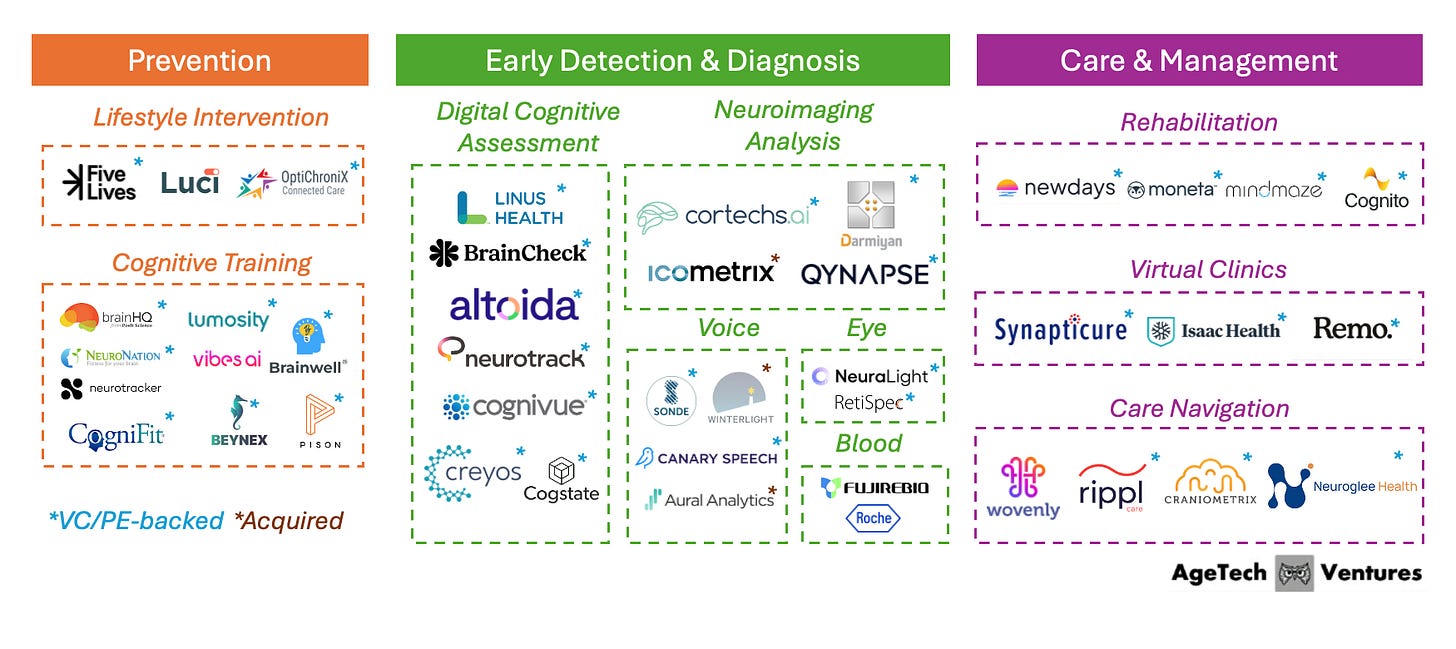

A market map of the technology solutions reshaping AD prevention, diagnosis, and care management.

Despite advancements, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains a devastating challenge of cognitive aging today. As the most common cause of dementia, 7.2 million Americans age 65+ live with the disease. In 2022, it was conservatively ranked the 7th leading cause of death in the United States, and that figure may be a severe underestimate as AD isn’t consistently captured in death certificates.

Alzheimer’s may also be the most feared outcome of aging. In a national poll of adults 50+, Alzheimer’s and dementia ranked as the most-feared health condition, ahead of cancer and stroke.

Because of the magnitude of its impact, tens of billions of dollars have gone into the search for treatment. Progress has been significant, but the disease is biologically complex, and drug development has been slower than many had hoped. For many families, Alzheimer’s is still a painful reality.

What is changing is not that we suddenly “solved” Alzheimer’s, but the ecosystem is reorganizing around earlier identification and longer-term support, and technology is increasingly central to how that happens.

In this post, I map the Alzheimer’s technology landscape across the three stages of the journey: prevention, early detection & diagnosis, and care & management. The goal is practical: to understand what categories are emerging, what’s actually getting adopted in the field, and where the bottlenecks to adoption are.

Why now?

For decades, the dominant cultural narrative (and often the clinical one) has been grim: once you’re on the Alzheimer’s path, there’s little you can do to change it.

This view is starting to change in three ways:

1) Prevention science is getting clearer: The 2024 Lancet Commission report identified 14 modifiable risk factors through a person’s life course, ranging from high LDL cholesterol to hearing loss, that could prevent or delay up to 45% of dementia cases. Most of these risk factors are generally correlated with better health outcomes, but some companies are going a step deeper and developing products that target cognitive health specifically.

2) New drugs are increasing the value of early diagnosis: Recently approved anti-amyloid drugs like Leqembi (Eisai/Biogen) and Kisunla (Eli Lilly), as well as other drugs in the pipeline, have the potential to slow the course of Alzheimer’s for many. But this category of drugs is meant for people with early-stage disease. This necessitates a system where we can detect disease earlier to successfully intervene, which is a capacity it lacks today.

3) Care can still change outcomes: Even after diagnosis, there is still meaningful room to improve daily function, caregiver burden, and quality of life when appropriate treatment and care programs are delivered. Previously, the fragmentation of AD care delivery had made coordination challenging, but more companies, aided by the recent CMS GUIDE introduction, are developing solutions to address that.

Thanks to the many experts who spoke with me about the latest developments in Alzheimer’s disease and technology. In particular, I would like to thank Reza Hosseini Ghomi (Medflow), who inspired me to write this article and was instrumental in shaping it, and Meg Low (Boston University), who helped me better understand the realities of implementing and validating these technologies.

Crash Course: Alzheimer’s 101

1) What is the difference between dementia and Alzheimer’s disease?

Dementia is a syndrome, or a set of symptoms that affect memory, thinking, and daily function. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a specific disease process and the most common driver of dementia symptoms. Other causes (e.g., Vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia) have different diagnosis and management pathways and are beyond the scope of this post.

2) What is the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s disease?

Scientists still do not fully understand the main cause of Alzheimer’s in most people, or why it starts when it does. The leading view is that it develops from a mix of age-related brain changes, along with genetic factors, health, lifestyle, and environmental influences.

APOE ε4 is the most well-known common genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s. About 25% of the general population carry one copy of APOE ε4, and about 2–3% carry two copies, which corresponds to the highest risk. Separately, rare genetic variants can cause early-onset Alzheimer’s, and people with Down syndrome have elevated risk.

3) How has Alzheimer’s traditionally been diagnosed?

Diagnosis often begins with clinical history and cognitive assessment, followed by additional testing to clarify cause. In the U.S., the “obvious” scalable entry point for this evaluation is routine cognitive assessments conducted during Medicare Annual Wellness Visits (AWV). Unfortunately, this still isn’t happening consistently: a nationally representative survey found that among beneficiaries who had an AWV, only 31% underwent cognitive testing.

To properly diagnose AD, clinicians look beyond cognitive performance to underlying brain pathology, most notably beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Structural neuroimaging (MRI/CT) is commonly used, but these are often insufficient to identify Alzheimer’s at the earliest symptomatic stages. More definitive diagnostic approaches have historically been cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and PET scans, but these are more invasive and costly procedures that are rarely used by non-specialists.

A major recent shift in AD detection is the approval of blood tests as a step to diagnosis. On May 16, 2025, the FDA cleared Fujirebio’s Lumipulse G pTau217/β-Amyloid 1-42 Plasma Ratio to aid in diagnosing Alzheimer’s in symptomatic adults (aged 55+). Though blood tests are not intended as a stand-alone diagnostic test, it is much easier to implement than other diagnostic evaluations.

4) How are pharmaceuticals used in Alzheimer’s treatment?

Drugs play a part in three areas of AD treatment:

slowing the disease early on,

easing symptoms for a period of time, and

treating complications common in dementia, like agitation or sleep problems.

No available drug cures Alzheimer’s or restores neurons that have already been lost.

The major recent advance has been anti-amyloid immunotherapy. Lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla) are approved for early symptomatic Alzheimer’s, and in clinical trials, they lowered amyloid levels and were associated with modestly slower decline on clinical measures over roughly 18 months. Uptake has been limited to date, in part because many clinicians and patients question whether the benefits justify the risks and monitoring burden, and in part because these therapies typically require IV infusions that can be logistically difficult to deliver. Next-generation anti-amyloid candidates in the pipeline hold promise to improve on these tradeoffs.

Alzheimer’s Tech Market Map

The Alzheimer’s tech landscape is being rebuilt around one simple reality: the earlier you can identify risk and underlying disease, the more options you have. That matters for reducing lifestyle-related risk, planning care, and using the new wave of disease-slowing drugs, which are most useful early on.

This market map groups Alzheimer’s technology by stages of the patient journey: prevention, early detection & diagnosis, and care & management.

Note: This map reflects how companies are positioning products across the Alzheimer’s journey, and it does not imply clinical validation or proven efficacy. The map also excludes pharmaceutical biotechnology innovation (therapeutics discovery/development).

Stage 1: Prevention

The prevention layer attempts to move dementia risk management upstream of specialty neurology by operationalizing what we already know: a meaningful share of risk is tied to modifiable factors across one’s lifetime, including cardiometabolic health, sleep, physical activity, mental health, social connection, and cognitive engagement. Most lifestyle intervention products that address these factors do not target brain health specifically, and the few that do are either grant-funded or early in traction.

Cognitive training can improve performance on trained tasks and may improve memory for individuals with MCI. “Brain games” were widely popular in the 2010s, but evidence that consumer brain-training apps prevent dementia remains limited and inconsistent, with mixed results for transfer to clinically meaningful outcomes. Many products are marketed as dementia prevention tools despite this evidence gap, and regulators have challenged overstated claims in the category (e.g., the FTC’s 2016 action involving Lumosity’s advertising).

Reimbursement in prevention is therefore still the exception, not the rule. For example, Medicare reimburses some evidence-based prevention programs aimed at cardiometabolic risk (e.g., the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program), but there is generally no standard Medicare reimbursement pathway for cognitive training programs, which are paid via out-of-pocket expense, employer wellness budgets or research funding.

Key Innovation Themes

The next generation of “mental fitness” products move beyond static brain games and toward closed-loop training powered by wearables, sensors, and real-time feedback. Companies like Pison and Vibes AI illustrate the direction of travel: cognitive training that is embedded into everyday routines, instrumented by hardware or audio-based feedback loops, and continuously personalized based on in-the-moment performance. The innovation is as much about engagement and habit formation as it is about the training itself, reducing drop-off by making progress visible and sessions easy to complete.

Commercially, many of these companies are choosing a “performance-first” wedge (athletes, gamers, younger professionals) rather than positioning as dementia prevention. That can be a practical way to drive adoption, while the evidence on long-term dementia prevention continues to mature.

Stage 2: Early Detection & Diagnosis

AD and dementia more broadly are frequently missed or diagnosed late. Although Medicare reimburses cognitive testing, imaging, and lab work, real-world diagnostic follow-through remains inadequate: about 40% of older adults with dementia symptoms either receiving a late diagnosis or no diagnosis at all.

Part of the problem is that clinicians are not always trained and well-prepared to conduct cognitive assessment. Digital cognitive assessment tools add value to providers and Alzheimer’s disease management by delivering standardized, objective, and often remotely deployable measures of cognition that can be repeated frequently with minimal staff time. Passive digital biomarkers can also help by making it easier to track changes over time between clinic visits and flag who should enter a diagnostic pathway.

Neuroimaging start-ups are also using AI to extract more Alzheimer’s-relevant signal from routine MRI and CT, helping to automate quantification of imaging biomarkers and helping generalist clinicians triage who needs further workup or specialist referral.

AI is unlocking new modalities for capturing cognitive and neurological signals with minimal friction, shifting detection from episodic testing toward continuous measurement. The most compelling approaches leverage data streams people already generate, from speech to device interaction, so that “screening” can happen passively without friction.

Key Innovation Themes

Voice is a leading example of a digital biomarker gaining traction in the space. Canary Speech and Sonde are building platforms that convert short, natural speech samples from everyday touchpoints (phone calls, telehealth visits, app check-ins) into repeatable signals that can be collected frequently without new hardware. The strategic value is not just detecting risk once; it is using high-frequency, low-burden data to support triage for next steps.

Stage 3: Care & Management

After diagnosis, dementia behaves less like a one-time medical event and more like a long-term care challenge across safety risks, caregiver strain, and progressive loss of function. Support at this stage is inadequate, and only 8.3% of caregivers of community-dwelling older adults living with dementia report receiving any caregiver training.

Companies in this layer are addressing this gap by building dementia-specific chronic care models via virtual or hybrid specialty care, care navigation, and function-preserving interventions, aiming to reduce crises and support caregivers.

The reimbursement pathways are generally strong for care & management solutions, but innovation is constrained by what insurers will pay for. Dementia care models commonly anchor around CPT 99483 (cognitive assessment and care planning) and therapy codes for cognitive function intervention such as CPT 97129/97130. Both require Medicare-enrolled clinicians to provide the services, which limits reimbursement for AI-only approaches.

A looming constraint for virtual rehab models is Medicare’s scheduled telehealth rollback. Under current CMS guidance, occupational therapists (OT) and speech-language pathologists (SLP) telehealth flexibilities extend only through January 30, 2026; starting January 31, 2026, OTs and SLTs can no longer furnish Medicare telehealth services. This creates meaningful pressure for companies delivering reimbursed cognitive rehab or speech therapy primarily to patients at home under Original Medicare, pushing many toward hybrid delivery models and greater reliance on Medicare Advantage or other risk-based contracts.

Key Innovation Themes

CMS’s GUIDE Model adds momentum by defining a more standardized dementia care-management package and enabling Medicare Part B providers to work with Partner Organizations, creating a clearer path for “plug-in” services to integrate into reimbursed care delivery. Companies like Rippl and Isaac Health have started to take advantage of the GUIDE structure with dedicated offerings, though the program is still early in implementation.

Open Questions

Will a breakthrough in AD drug development occur to truly pull early detection forward to change the trajectory of AD?

A true “pull” from therapeutics requires more than another modestly effective drug that measures efficacy through cognitive tests, which are criticized to have bias and limited real-world implications. It requires a step-change in real-world value: a notable delay in disease onset or a noticeable change in a patient’s functional capabilities. If the next wave of therapies materially improves outcomes and is practical to deliver, early detection becomes an enabling infrastructure investment: routine cognitive monitoring, streamlined biomarker pathways, and earlier specialty engagement start to look cost-effective rather than optional.

On the other hand if breakthroughs remain incremental, early detection will still expand, but the center of gravity may stay with post-diagnosis care planning, and diagnostics will primarily still be used to reduce uncertainty and guide support, rather than to unlock transformative treatment.

Who is the buyer for multi-year dementia risk reduction?

The buyer question is fundamentally about time horizon and churn: the most natural institutional buyers are risk-bearing organizations with older populations and clear utilization incentives (Medicare Advantage plans, ACO-like primary care groups, integrated delivery systems), but they still need evidence that programs reduce costs through intermediate outcomes they can measure sooner.

For individuals and families, willingness to pay tends to spike only when risk feels concrete or when symptoms begin, which is why many companies either (a) anchor the business model post-diagnosis (where urgency is high) or (b) bundle “brain health” into prevention categories people already buy for immediate value.

As early risk detection becomes easier, will individuals opt in as active operators of their risk, or opt out due to fear, stigma, and the burden of “knowing”?

As monitoring and biomarker tests get easier to access, people likely won’t all move the same way. Some will opt in, especially if Alzheimer’s feels personal through family history or a strong prevention mindset, because information gives them something concrete to act on. Others will opt out, not because they don’t care, but because “knowing” can feel heavy: fear of what the result might mean, uncertainty about what to do next, privacy concerns, and stigma.

This stigma already affects behavior today by keeping people from seeking evaluation and diagnosis. In a survey of 1,300 individuals aged 50+, only 7% had used DTC genetic testing for APOE status to understand their risk of developing AD. If opting in is going to become the norm, the experience has to feel safe and useful with supportive counseling, real next steps, and guardrails that reduce the social and practical risks of learning you’re at higher risk.

Closing Thoughts: Who will Win

The next chapter of Alzheimer’s innovation will be defined less by any single technology and more by whether the ecosystem can connect detection to outcomes. Prevention science is clarifying what can be modified, new therapies increase the value of early identification, and care-management pathways are making longitudinal support more scalable.

Together, these forces are pulling Alzheimer’s care toward an operating model that looks more like chronic disease management: continuous measurement, staged escalation to definitive testing, and sustained care navigation that supports both patient function and caregiver resilience.

The companies that matter most will be those that close the loop. It is not enough to predict risk or detect early change; the product must reliably answer “what now?” for clinicians, payers, and families. That means integrating into practical workflows, demonstrating benefits that show up in utilization and quality-of-life metrics, and designing for the human realities of fear, stigma, and uncertainty. If the industry can do that, earlier detection becomes empowering rather than paralyzing, and the Alzheimer’s journey becomes more navigable even before we reach a definitive cure.

Reading this made me realize how powerful earlier, gentler detection could be for families who just want clarity before things get worse. Great piece, Jenny!

This is an excellent market map. What I appreciate most is that you frame Alzheimer’s as a journey with different bottlenecks at each stage, rather than a single “diagnosis moment”. The “why now” section is spot-on: as blood-based biomarkers and disease-slowing therapies move earlier, the value shifts toward earlier, scalable detection and triage, not just specialist-only workups.

The next frontier is implementation science: how we make screening/monitoring accurate enough to avoid iatrogenic harm (false positives, anxiety, over-referral), equitable across literacy/language/tech access, and integrated into real workflows like AWVs without adding burden. I also love that you don’t stop at “prevention + diagnostics”; you treat post-diagnosis care as a chronic-care problem where outcomes (function, caregiver strain, time-at-home) are still highly modifiable, and you connect that to real reimbursement pathways (GUIDE, 99483, rehab codes) and looming constraints like telehealth rollbacks.

Tools are only as good as the system that stitches them into a coherent, trustworthy care pathway!